Batman: Mask of the Phantasm

Story by Alan Burnett

Screenplay by Alan Burnett, Paul Dini, Martin Pasko, Michael Reaves

Directed by Eric Radomski and Bruce W. Timm

Original Release Date—December 25th, 1993

Plot: When a new vigilante starts killing gangsters, Batman is suspected of the crimes. While the police lead an all out manhunt for the caped crusader, mob boss Sal Valestra turns to the Joker for protection. Meanwhile, Andrea Beaumont, Bruce Wayne former love, returns to Gotham, sparking memories of a time Bruce almost chose not to become Batman.

Batman: Mask of the Phantasm is in many ways a distillation of the themes, plots, and tropes of Batman: the Animated Series. It’s a story of long delayed vengeance that uses flashbacks featuring important moments in Batman’s origin, like “Robin’s Reckoning” and “Night of the Ninja.” Bruce has a crisis of faith over whether his parents would want him to be Batman, as he did in “Nothing to Fear” and “Perchance to Dream.” The police hunt down Batman for crimes committed by a different weird figure of the night, as they did in “On Leather Wings.” Bruce seeks the approval of surrogate father figure Carl Beaumont, Andrea’s dad, as Bruce has done… well, a lot. And Andrea Beaumont, for her part, is a combination of all of Bruce’s love interests so far, a socialite who’s secretly a supervillain, an old flame who reminds Bruce of a moment of joy in his life, and a hyper competent fighter who is maybe too attached to her father. And, of course, the Phantasm is the archetypal example of the most common recurring trope of the Animated Series, the dark reflection of Batman.

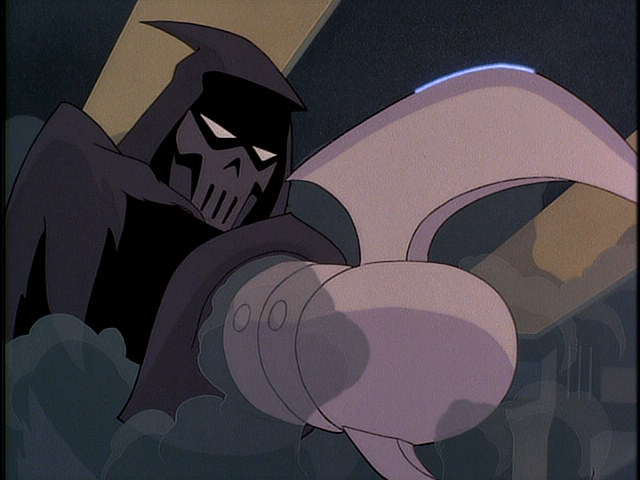

Mask of the Phantasm is the revenge origin in its purest form: Batman fights a sympathetic vigilante whose methods he finds too extreme. The Phantasm (who is never actually called “the Phantasm” within the film) is almost exactly the same as Batman. Similar motivating event (the death of her father), similar civilian identity (rich socialite), even an almost identical costume, with the inversion that Batman is a devil who saves lives, while the Phantasm is an angel of death. The Phantasm could just as easily have ended up being another hero like Robin or Batgirl, except, thanks to the looser standards and practices for a movie rather than a network show, that the Phantasm kills, and Batman does not.

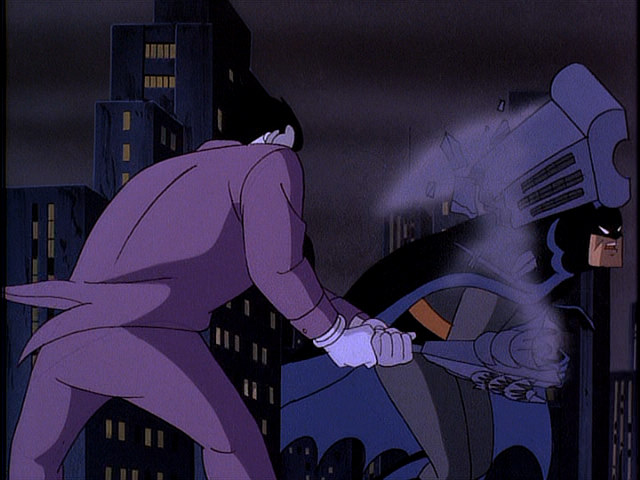

The directors, series creators Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski, really take advantage of their freedom by ramping up the violence and sex. After watching sixty five episodes where the “deaths” mean falling into water, never to be seen again, three people explicitly killed, including one Jokerized corpse, is viscerally shocking. Batman bleeds, a lot. The Joker loses a tooth. The whole thing is much more brutal than usual, but never slips into gruesome. While the Phantasm has a razor-sharp scythe, she never cuts human flesh with it. In the other direction, Bruce and Andrea definitely spend the night in bed together. Their courtship in flashback is also a lot more sensual than the series can usually get away with (Poison Ivy excluded). Andrea falls on the grass and her skirt lifts in a suggestive, leg revealing manner just before Bruce jumps on top of her. Bruce even manages to tell someone “you know where you can stick it.”

But the real advantage of the movie over the series is the budget. Mask of the Phantasm started as a direct-to-VHS production, but when Warner Bros. studio executives saw how popular the cartoon was, they gambled they could use Batman to break into the lucrative theatrical market for animation that Disney had a stranglehold on. So they bumped up the budget to six million dollars, almost all of which went into the animation. Spectrum and Dong Yang put in their best work yet here. From the computer generated opening credits (which were fancy and expensive in 1993) to the harried chase through the construction site to the final, knockdown, dragout battle between the Joker and Batman in the remains of the World’s Fair, each frame of this movie is gorgeous, and the motion is fluid and dynamic.

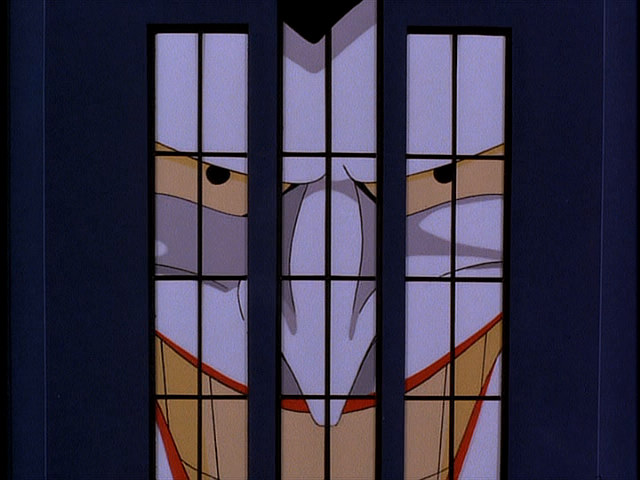

In terms of acting, Kevin Conroy, Mark Hamill, Efrem Zimbalist Jr., Bob Hastings, and Robert Costanzo are the definitive voices for Batman, the Joker, Alfred… blah blah blah. They all do a fine job with their parts, but honestly none of them really turn in a better performance than their usual high quality work. It’s with the guest stars where casting director Andrea Romano shines (Jesus, did I really review 65 issues without mentioning Romano? Bad reviewer! Bad!) She fills the members of Sal Valestra’s gang with great actors from gangster B-movies, Abe Vigoda, Dick Miller, John P. Ryan, and Stacy Keach Jr. She even got the asshole from Die Hard, Hart Bochner, to play the jerk of a councilman, Arthur Reeves. The great cast of heavies plays on a central metaphor of Batman, the ordinary gangsters overshadowed by the introduction of supervillains.

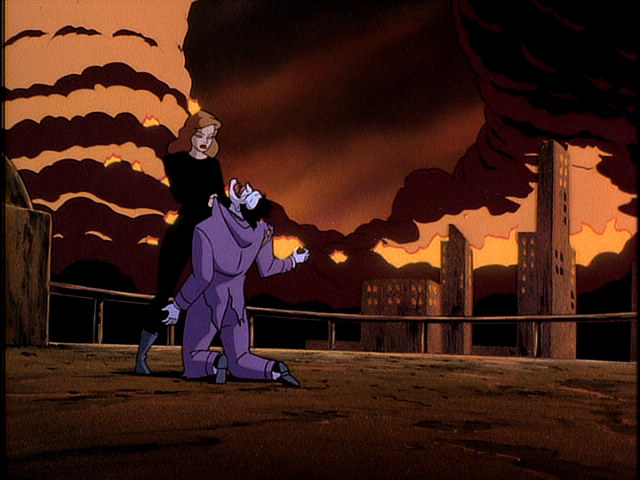

The standout, of course, is Dana Delaney as Andrea Beaumont. Her flirty encounters with college age Bruce Wayne and her angry clashes with the Batman of today demonstrate a complicated, whip-smart, driven woman with secrets of her own. It’s easy to see from this performance why Delaney would be cast as Lois Lane later on. However, as good as she is when she’s playful or emotionally distraught, Delaney’s not quite as good when she needs to be the cold machine of vengeance Andrea becomes in the final act.

The mystery of who is behind the mask of the Phantasm is fairly well done, but not done fairly. Certainly, there’s reasons to suspect the Phantasm is Carl Beaumont. Stacy Keach provides his voice and the voice of the Phantasm while masked. And Mask of the Phantasm is loosely based on Batman: Year Two, where the father of Batman’s love interest is the scythe-wielding vigilante the Reaper. Even if you guess that Carl is already dead, Arthur Reeves, who is eager to throw suspicion on Batman, has reasons to silence the Sal Valestra gang, and is a smarmy jerkface, makes a good red herring. However, having Andrea arrive in Gotham after the first Phantasm attack just isn’t cricket. Batman claims she specifically did that to give herself an alibi, but really, the only people who would be fooled by that is us, the viewing audience. Anyone in Gotham could have been fooled by a phone call and a little lie. It doesn’t help that the Joker ends up being a better detective than Batman. Even with inside information (that the three mob bosses are connected to Carl Beaumont and that Carl Beaumont is already dead), the Joker figures out who the Phantasm really is long before Batman does. It’s not clear that Batman ever figures out the Phantasm isn’t Carl until he sees Andrea in the costume.

The flashbacks create background not just for Bruce’s relationship with Andrea, but for the Animated Series as a whole. In line with “Robin’s Reckoning,” Mask of the Phantasm establishes that Bruce has been Batman for ten years. Borrowing elements from Batman: Year One, we see Bruce tried the sane (or saner) course of being a non-costumed vigilante before becoming Batman, but found people are not as scared of a dude in a balaclava as they are of a dude dressed like Dracula. And lining up with Tim Burton’s Batman, we see the Joker was a mob hitman before his dunk in the chemical bath. There’s also the suggestion that maybe Batman isn’t helping Gotham that much. Ten years ago, the World’s Fair was a celebration of how awesome the future is going to be, and now it’s a rundown hellscape that houses a literal mad man.

The very Batman: the Animated Series twist on Batman’s origin is how much Bruce does not want to be Batman. Batman, Bruce says, is the opposite of being happy. The opposite of having a family. Arthur Reeves says Bruce only gets involved in relationships he know will fail (hello, Selina), unknowingly implying Bruce does so because he does not want emotional entanglements to distract him. Certainly, the scene of Bruce putting on the Batman mask for the first time, and Alfred’s horrified expression, imply that once Bruce becomes Batman, he has given up the chance at a happy life. Except, we know Batman does have emotional attachments, to Alfred and to Dick Grayson, and those attachments make him stronger.

That brings up some questions of chronology. Except for the use of the Batsignal (installed in “The Cape and Cowl Conspiracy”) Mask of the Phantasm feels like it should take place before “On Leather Wings,” or maybe in place of it, “Christmas with the Joker,” and “Nothing to Fear” as the series’s pilot. The police suspect Batman of murder, Bruce still questions whether he’s making the right choices, and the only supervillain is the Joker. Batman questioning whether he can have a family after raising Dick as his son for nine years is a little weird. After the introduction of Batgirl and Zatanna, it gets downright nonsensical.

But the real problem with Mask of the Phantasm is the disappointing final act. Not that the brawl between the Joker and Batman isn’t spectacular—it is, probably the best confrontation they have in the whole series—but it’s not the final battle the film has been building to. The Joker isn’t even introduced until halfway into the movie. The central conflict is between Batman’s (comparatively) merciful, tempered version of crime-fighting and the Phantasm’s take-no-prisoners, kill them all approach. The final fight should have been between the two leads, with Batman in the uncomfortable position of protecting the Joker. But instead of that confrontation, which would have tested Batman’s commitment to doing the right thing, Batman sends a multiple murderer home so he can have a fight we’ve seen seven times already.

The film never manages to get around to explaining why killing bad guys, such as the Joker, is a bad idea. Alfred moralizes about how “vengeance blackens the soul” and Batman “hasn’t fallen in the pit,” but no explanation of what exactly that means in terms of masked vigilantism. In the final confrontation, Batman says he’s willing to kill both the Joker and himself if that’s what it takes to stop the Joker. So how is that different from what Andrea Beaumont is doing? In a moment of anti-climax, Batman hardly even tries to stop Andrea from disappearing with (and presumably beheading) the Joker before Batman accidentally escapes the exploding theme park by falling into a sewer.

The ending leaves so many questions. Apparently all of Gotham knows the Joker has set up shop in the abandoned World’s Fair, so why is Batman only going after him now? Why is Andrea only coming back to Gotham now to extract vengeance, if her father died at least two years ago (i.e. before the Joker became the Joker)? Where did she get power armor that lets her disappear in a cloud of smoke, cut through steel, and outrun the Batplane? In a half hour episode, such elisions make sense, but with 76 minutes to play with, you can spend a couple explaining the plot.

In the end, the anti-climactic ending robs Mask of the Phantasm of any meaning. We watched Batman fail to stop another vigilante from killing people, and I’m not sure that we’ve learned anything from the experience. Mask of the Phantasm is gorgeous. Mask of the Phantasm is well acted. It’s funny, and scary, and thrilling, but in the end it’s also kind of pointless. Why did we do that again?

Steven Padnick is a freelance writer and editor. By day. You can find more of his writing and funny pictures at padnick.tumblr.com.

Echoing some of your thoughts, I like most of this movie, except the ending. It seems to me that Batman goes after Joker at the end simply becuase he was Joker, and for no other reason. In fact, Joker is the victim in the piece, and only protecting himself.

It would have been interesting to where Phantasm vs. Joker would have gone without Batman interfering.

The other place I had a problem with was during the construction site chase. Batman is stopped by tear gas? We have seen him produce a variety of gas masks before. Either Batman got a little incompetent, or Gotham Police got super competent just for this one sequence.

Other than that, lovely piece; and at the risk of getting lynched, I will say that it was better than the live-action movies.

Honestly, it’s the same damn movie as Batman Begins, and I think Radomski & Timm’s film is better than Nolan’s.

http://www.sff.net/people/krad/batsbegins.htm

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

Who’s lynching who now?

THIS.IS.THE.BEST.BATMAN.MOVIE.EVER.

I always did find the climax a little unfocused, but I hadn’t seen it quite so negatively as this. Still, you make some good points.

I also felt the animation was not as great as I’d hoped. Spectrum and Dong Yang did pretty good work, but it didn’t feel that much beyond the best of their work on the show, and it wasn’t as good as TMS would’ve done if they’d gotten the gig. (TMS did animate Batman Beyond: The Return of the Joker, and did utterly gorgeous work there.)

What really surprised me here is that they didn’t even do a proper depiction of the origin story. The show had to skirt around the murder of the Waynes due to FOX censorship, resorting to symbolic dream sequences and newspaper headlines, so I thought that once they were free of such strictures, the creators would take the opportunity to tell a proper origin story. But while the movie is about the origin of Batman per se, it still treats the Wayne murders in the same indirect fashion as the show. Which means that we never actually got a depiction of that event in the DC Animated Universe. The closest we got was in Justice League Unlimited: “For the Man Who Has Everything,” wherein Batman hallucinated an alternate version where Thomas Wayne turned the tables on the gunman and beat him senseless.

You left out the music credits. The score is credited to Shirley Walker, but the soundtrack album lists a lot of her team members from the show as orchestrators, including Lolita Ritmanis, Peter Tomashek, Harvey R. Cohen, and Michael McCuistion. So I’ve always wondered if it was really more of a collaboration with Walker composing the basic themes but the other composers creating the specific cues based on those themes. To be honest, I don’t find the music as impressive as Walker’s best work on the show either.

Still, MotP was better than any of the live-action Batman movies we were getting at the time. Ironically, it was the animated movie that was more naturalistic while the live-action movies wallowed in cartooniness. I always regretted that we didn’t get more animated theatrical features from DC/Warner Bros.

I like the rest but LOVE beyond words that joker loses a tooth!

I agree this is probably a prequel to the show proper, if only becaus of the construction site scene. THAT’S what made Batman start loading up on gasmasks and breathing gear. It also explains the relative competence of the Police, and why they’re so quick to jump to conclusion in “On Leather Wings” THIS incident must still be very vivid for them.

Good rewatch/review with some good and fairly objective points, even if I never have viewed the film’s problematic points – including the climax/ending – so negatively.

I loved everything about the film: story, acting, character study, even if the the theme of vigilantism itself could have been explored more. And the music, though not as thematically diverse as the series itself, is still, in my opinion, superb (the opening titles alone are quite a treat).

Despite its minor faults, I still think Mask of the Phantasm is the best Batman film produced so far, period.

@ChristopherLBennett

Not that the Batman animated series crew couldn’t have done a great rendition of Batman’s origin, but I think it is so well-known at this point that it’s not really necessary. Batman: Lost Parents, Fights Crime; this is practically etched into the public unconscious.

@9: But at the time, it had only been depicted on screen twice before — once in the Alan Burnett-scripted “The Fear” in The Super Powers Team: Galactic Guardians in 1985, and once in the Tim Burton movie, which tampered with it by replacing Joe Chill with Jack Napier. In the comics, it’s an iconic scene that many writer/artist teams have depicted and interpreted over the decades. This is one of the things that superhero comics do: retell iconic origin stories and allow different creators to put their own spin on them. The DC Animated Universe is widely and justifiably considered the most successful and important animated interpretation of Batman and the DC Universe, the pinnacle of artistic achievement in superhero animation, yet its writers and artists never really got a chance to put their own imprint on this integral part of Batman’s origin myth. (Well, its writers did, since Burnett wrote “The Fear” and Paul Dini would later write the classic “Chill of the Night!” episode of Batman: The Brave and the Bold. But the DCAU team working together in that particular milieu never did.) That feels like an oversight.

@10 Maybe it is telling, rather than an oversight. Maybe we don’t really need to see that onscreen.

The death of Bruce Wayne’s parents is the trigger than sends him on the path to becoming Batman–but it’s not defining for Batman in the same way that say, Uncle Ben’s death weighs constantly on Peter Parker. Batman is not responsible for his parents’ death; he remembers them, but he shouldn’t be overwhelmed with guilt.

I am not a fan of the interpretation of Batman that he is just a

dysfunctional child who never got past his parents’ death. Batman should not be an obsessive neurotic, like the Burton/Keaton version.

He’s not obsessed with revenge either–I think it is probably a mistake that Joe Chill even exists, and it’s wise that he’s not really a presence in the DCAU. It’s not important for his parents’ murderer to have an identity, because it doesn’t add anything to Batman. There is no end to his quest–bringing Joe Chill to justice is far beneath Batman.

Batman is the Caped Crusader. He is out to defeat Crime itself.

He has personal reasons for what he does, but his quest is ultimately larger than himself–Batman is an ideal. That’s why he has an entire family of superheroes inspired by his lead.

Not to say that it’s wrong to depict the event, but I think focusing too much on the death of Wayne’s parents is missing the boat a bit.

@11: I absolutely agree that Batman should not be defined by seeking revenge on his parents’ killer specifically — which was one of the many, many things I dislike about Burton’s version. But the actual loss of his parents was a defining event in his life. Even if he’s not obsessed by it — and again, I agree he shouldn’t be — it was an event that changed him forever and set him on a very different path than he otherwise would have followed. It was the event that created his sympathy for the victims of crime and inspired him to devote his life to protecting them. Even for a functional, emotionally healthy Batman, it’s still the moment that drives everything that follows. (Even the 1966 Batman sitcom acknowledged in the pilot that Bruce’s “own parents were murdered by dastardly criminals.”)

It’s also just a matter of what you’re allowed to get away with in animation. It was damned impressive that Burnett and the makers of “The Fear” were able to get away with depicting a double murder on Saturday morning TV in 1985 — granted, they cut away to flashes of lightning rather than showing the gunshots, but their focus on the look of horror on young Bruce’s face actually made it far more potent and wrenching than if they’d actually shown the bullets hitting and the bodies falling. For a kids’ cartoon, especially an incarnation of the Super Friends franchise, to get away with something like that was amazing. But B:TAS was under much stricter censorship on FOX Kids. Their avoidance of showing the Wayne murders wasn’t due to artistic discretion on their part, it was due to the network forbidding them to depict it. So I’d expected that once they were doing a feature film and freed from that censorship, they’d do the one thing they’d been so persistently kept from doing before and actually tell us outright what had happened to Bruce Wayne’s parents rather than dancing so gingerly around the issue. I’m just surprised that they didn’t take that opportunity, is all.

@12: An interesting point on the Joe Chill issue is in fact made in Batman: Arkham Asylum, which is in many ways a spiritiual successor to both the comics and Batman: TAS (eg through involement of Dini, Conroy, Hamill and so on). When Batman is under the influence of Scarecrow’s gas and begins reliving the night of his parents’ death, Joe Chill’s voice is distorted. This could be due to the trauma Bruce experienced as a child, or it could be that Joe Chill himself as a person/character is, by this point, inconsequential; it is Crime that took Batman’s parents and that is the target of his crusade.

I agree that the ending slugfest with the Joker didn’t fit with the rest of the film. When I first saw the movie (which was well after it had aired; actually, probably not until after Batman Beyond), I was kind of annoyed that the Joker was in it at all. It felt more like a marketing, “This is the most famous villain, so he’ll more reliably put butts in the seats”-type decision.

But I absolutely loved the scene where Bruce broke down in front of his parents’ grave. His lamenting that he “never counted on being happy” broke my heart but also hits on what so often separates Batman from those he fights alongside: he often can’t allow himself to be happy and also be Batman.

-Andy Holman

@14: I think it was justified having the Joker in the movie, because he’s pretty much the poster child for the argument over killing bad guys, as represented by Phantasm, versus taking them in alive, as represented by Batman. So it makes sense that he should be at the center of the Batman/Phantasm conflict. The problem is that it ended up being a Batman/Joker conflict with Phantasm marginalized, and that it didn’t really have a resolution short of stuff blowing up.

Considering all the hype this movie got, I was actually kind of disappointed with it. Oh, I enjoyed it to be sure, but it wasn’t the best Batman movie as many claimed. At least, it wasn’t for me. One thing that greatly annoyed me is that Bruce never made a true choice between Batman and a normal life. Andrea made that choice for him by returning his ring and later becoming a masked killer. Him wavering is understandable before he was established as Batman and truly understood the crime element of Gotham, but after doing all this for ten years? Not as believable for me, especially with how much of a control freak Batman is with his belief that only he can save Gotham. It came across that the only thing between Batman and retirement is nostalgia and a nice pair of legs.

And what was with that ending? Andrea killed two people and was going for a third, and Batman just let her go? What happened to his moral code? And as Andrea escapes with the Joker, what happens there? Obviously he doesn’t die. Does he trip on yet another random roller skate, fall into the water and just escape?

@16: There’s a Paul Dini-written sequel comic, Batman & Robin Adventures Annual #1, that shows what happens after the explosion. Andrea escapes down a sewer grate with the Joker in tow, and she’s about to kill him when the memory of Batman’s “What will vengeance solve?” makes her hesitate just long enough for another explosion to distract her, whereupon the Joker does, as a matter of fact, fall (or dive) into the water and just escape.

The Joker must be the world’s strongest swimmer with the amount of escapes he makes via water. Would have been nice for them to have put that in the movie rather than making us go to a tie in comic to find out what happens.

@18: Well, knowing how the Joker escaped certain death is beside the point. It’s just something he does, a running gag of his character. It’s like how we don’t need to know how Batman escaped the chains off-camera in “Harley and Ivy.” The fact that he’s Batman is all the explanation we need.

So the comic wasn’t essential, it was just a bonus. The sequence of Andrea and the Joker escaping the blast was just 2-3 pages long, and we already knew from the movie that Andrea survived. The rest of the story was a sequel to the film, featuring the return of Phantasm (with some mystery over who was wearing the costume this time).

You have my respect. I enjoy this movie quite a bit but I don’t feel it’s the perfect Batman experience fans claim it is and certainly not the best movie featuring Batman.

There’s also the question of how Batman managed to clear his name by the end. Besides him, Joker, and Andrea, the only other person who knew about the Phantasm was Arthur, who was in no condition (or inclination) to testify on his innocence.